But there are some cheap solutions to try to save money. We’ve looked at where you are likely to be losing the most energy in your home and come up with some simple solutions to help save money on your bills and keep warm this winter.

1. Doors

Warm air wants to leave your home and will find any nook and cranny to do so. As it does, cold air is sucked in to replace it, causing draughts. It makes your home cold and wastes energy.

Shutting doors and closing windows may not be enough as any gaps in the frames allow warm air to escape – and that costs money. On this thermal image, the draughts show up as the coldest areas around a front door.

The coolest temperatures are black, purple and blue and the draughts are shown around the door in these colours, says James Richardson, of IRT Surveys – which uses thermal imaging to help home owners identify where heat is being lost.

The letter box, often an escape route for hot air, appears warm (red and yellow colours) so it is likely to be well-sealed and insulated.

But by simply adding a draught excluder – or even a rolled up towel – the draughts can be blocked, as we can see in these before and after images:

Energy firms and energy-saving campaigners agree one of the simplest solutions to keeping out the cold is to use a draught excluder. Combined with draught-proofing of windows and doors, it could help cut around £25 a year off your bills.

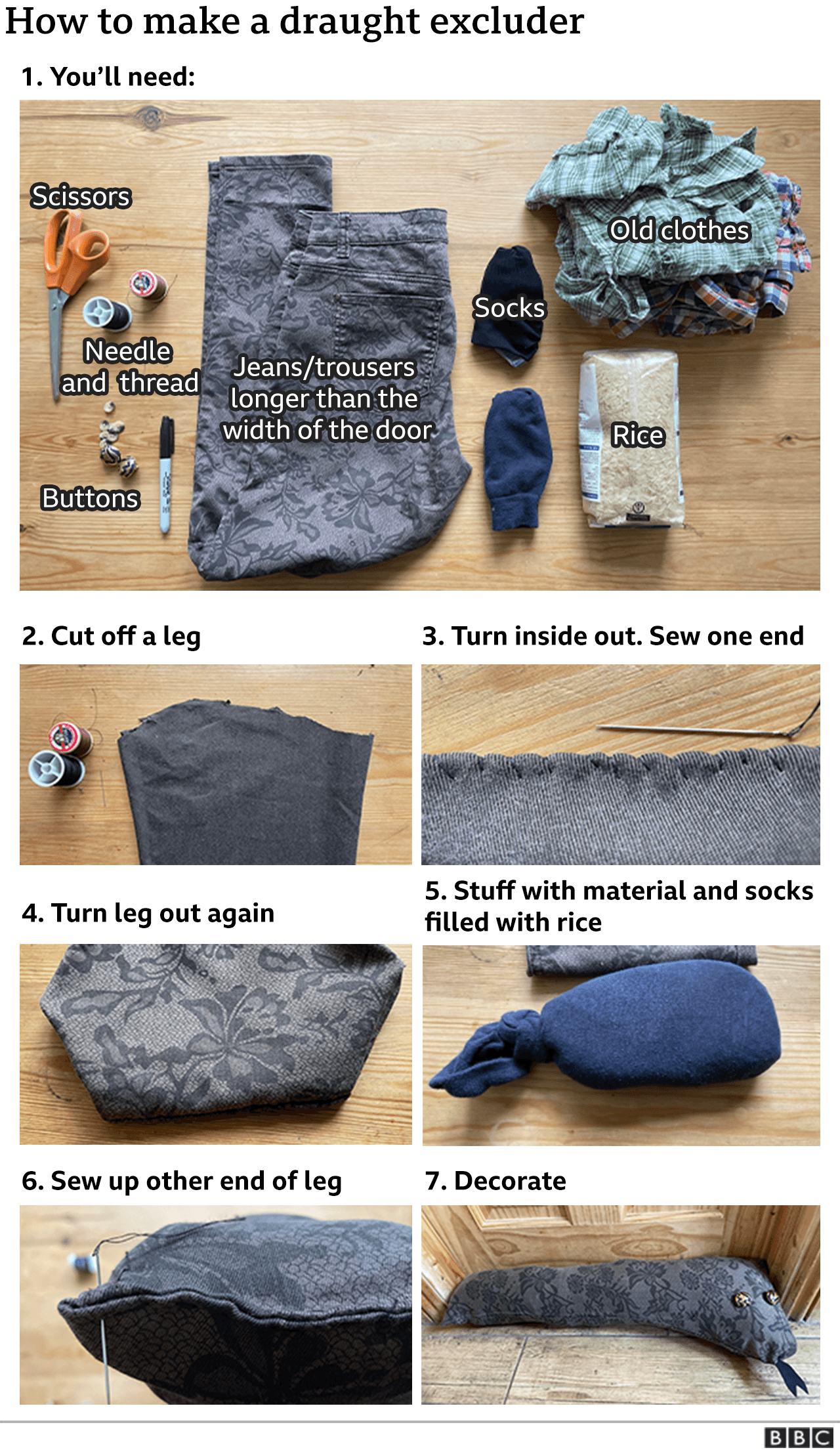

Having a rolled-up towel by the front door may not be the most attractive household feature, but you can always try to make and decorate one yourself.

It is important to make sure the draught excluder covers the width of the door. And for a no-sew method, use strips of the discarded material to make ties and tie up each end of the trouser leg instead.

If you don’t fancy cutting up your jeans you could just use a rectangular piece of material to make a tube and fill in a similar fashion. You’ll end up with a more regular-shaped excluder.

For the really crafty, or Team GB Olympic gold medal-winning divers perhaps, Home Energy Scotland have a pattern for a knitted version.

2. Windows

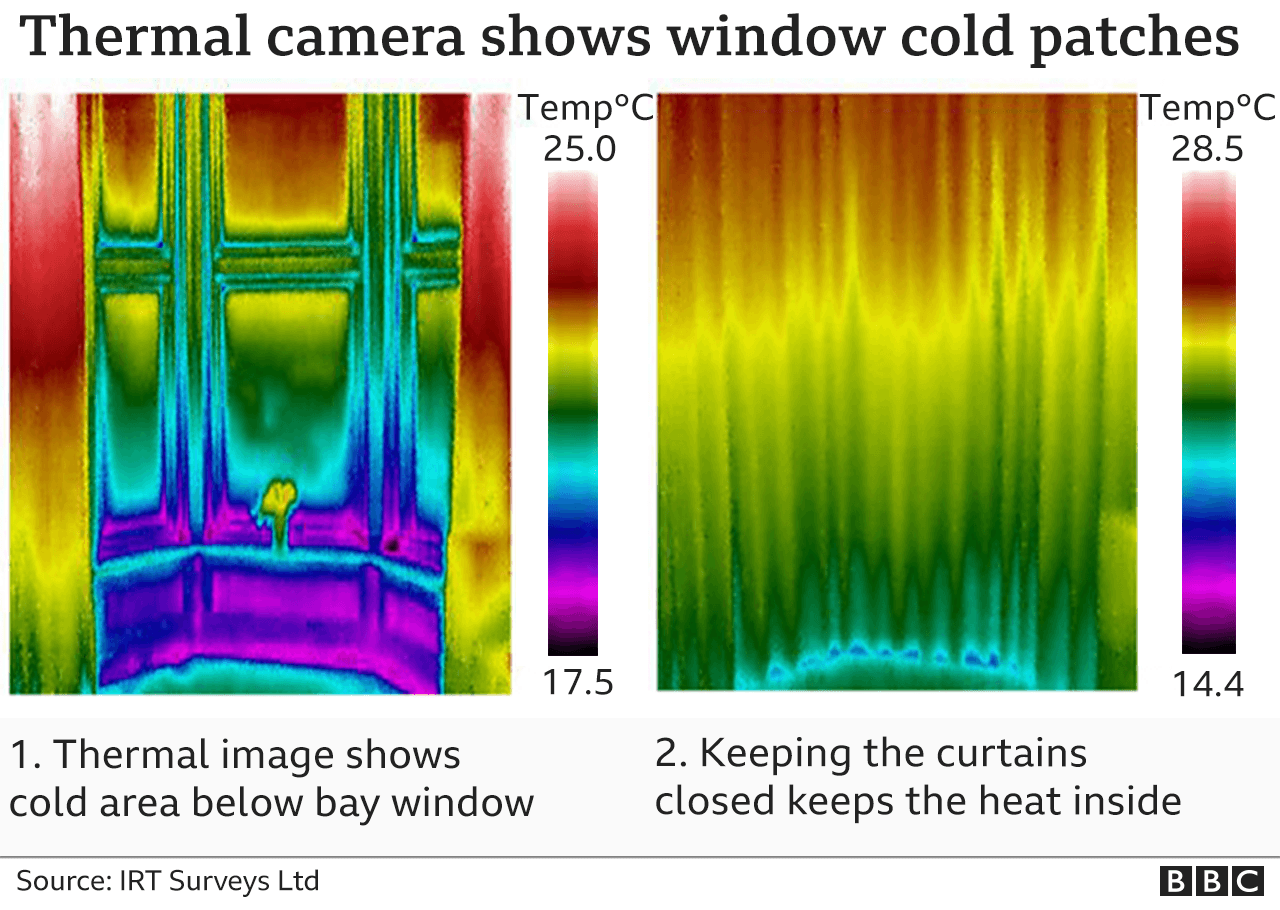

Badly fitting windows or single panes of glass are another place heat is often lost.

If you can’t get windows replaced with double glazing, the Energy Saving Trust says it is worth getting some heavy curtains to help keep the heat in the room.

Again, the thermal images show how closing the curtains traps that heat in with you.

You may not want to sit in the dark all day, so look out for cheap DIY kits available that use a thin plastic sheet to cover the window, blocking draughts.

They are sometimes shrink-fitted into place with a hairdryer and can be removed and replaced as required.

3. Loft hatch

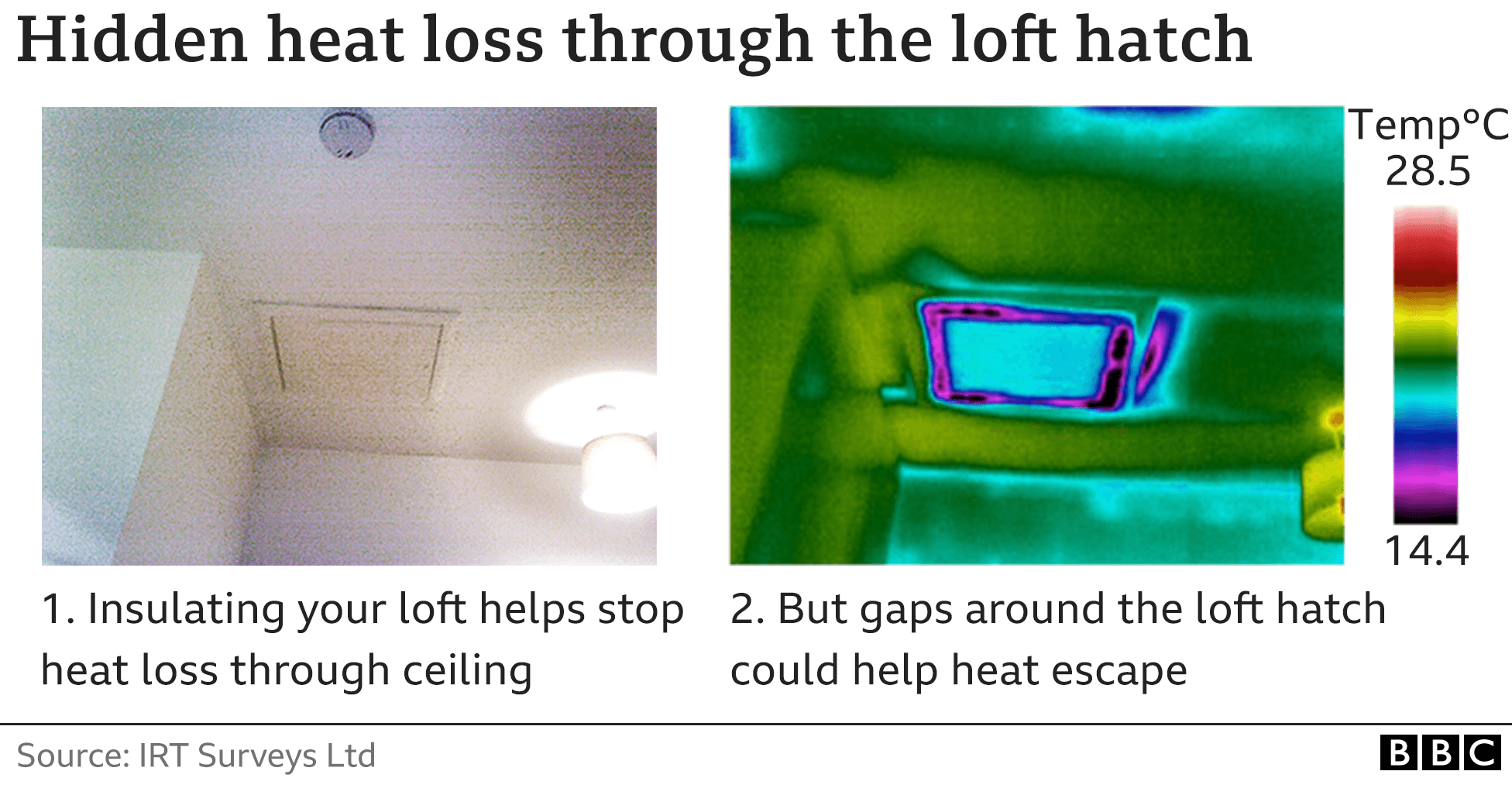

Insulating your loft is like wearing a woolly hat – trapping the warmth below to keep you cosy. However, that hatch is just like any other door and needs attention too.

Even James was surprised by the thermal image showing heat being lost around the frame. But it’s an easy fix, making sure it is snugly insulated around the edges.

One suggestion online is to glue a plastic bag to the back of the hatch, fill it some of the loft insulation and then seal it up. It should help insulate the hatch and flop over the edges when you pull it shut, stopping draughts escaping.

4: Behaviour

There are lots of little things we can do around the home that will help save energy and money that just require tweaks to our behaviour rather than installing, fitting or making anything.

Most energy companies will install a smart meter for free so you can help monitor your energy use and spending.

But there are other small changes to your daily routine that cost nothing and save energy. The obvious ones are spending less time in the shower (potentially saving about £10 a year), turning off the lights (£14) or turning down the thermostat (saving up to£55).

The Eco-Experts blog recommends “heating the humans, not the building” – so perhaps don’t keep the central heating on all the time if you’re not cold, and don’t heat rooms you’re not in.

Other ideas include:

- Put lids on pots and pans when cooking – it’ll be done quicker

- Use a microwave to reheat food rather than the oven

- Don’t overfill the kettle. Filling a kettle for two cups of tea rather than boiling a full kettle could save you around £45 a year

- Defrost your fridge – it will work more efficiently

- Buy a smaller telly – Age UK says in general smaller TVs cost less to run and plasma screens use more electricity

And finally there is the old favourite – repeated by parents down the ages and still on the advice the elderly by Age UK – if you’re cold, put on an extra layer – several thin layers of clothing will keep you warmer than one thick layer, as the layers trap warm air between them.

Source BBC