Straddling the seismically active Pacific Ring of Fire, Indonesia is one of the most geologically active countries in the world, with churning molten rock beneath the archipelago triggering about 1,000 tremors a month. The heat generated by movement in the Earth’s bowels can be harnessed. Where water seeps into the ground, it warms up, creating energy that can power homes and industry if you drill deep enough.

In 1904, Italian scientist Piero Ginori Conti became the first person to use this type of energy to power several light bulbs. More than a century later, geothermal power has become an important source of renewable electricity from the United States to the Philippines, but Indonesia wants to rise above them all.

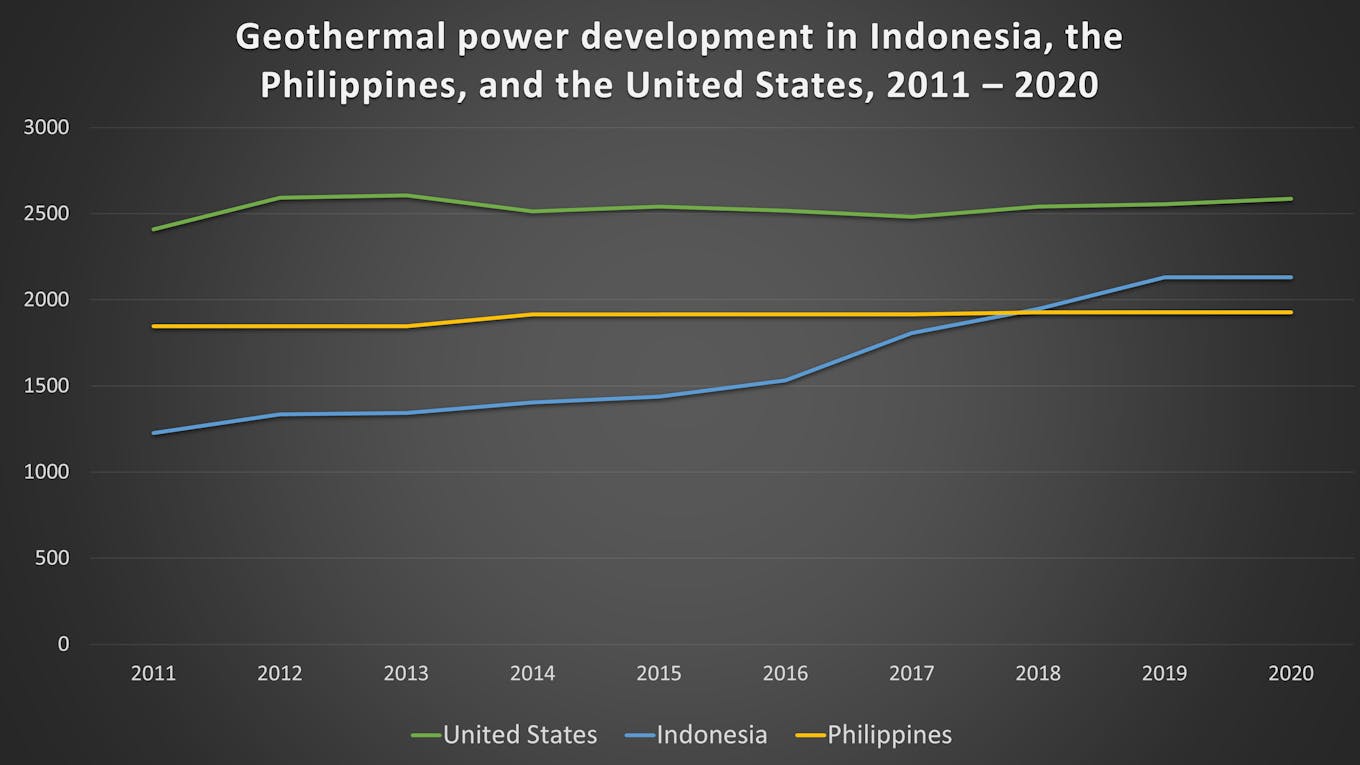

Home to 40 per cent of the world’s geothermal resources, Indonesia’s government has identified more than 300 sites with an estimated 24 GW in geothermal energy reserves—the world’s largest—across islands including Sumatra, Java, Nusa Tenggara, Sulawesi and Maluku. Most of this remains untapped. Three years ago, it overtook the Philippines to become the second-largest geothermal power producer globally. Now, it only tails the United States, which has a capacity of 2.6 GW.

In a push to become the world’s geothermal powerhouse, Southeast Asia’s biggest economy aims to install 8 gigawatts (GW) of geothermal capacity by 2030, up from about 2.1 GW currently.

Geothermal plants use steam from underground reservoirs of hot water to spin a turbine, which drives a generator to produce electricity. An inexhaustible source of heat, geothermal is relatively clean and does not emit carbon dioxide or other greenhouse gases, doesn’t produce a lot of waste or make a large footprint on land. Unaffected by the whims of nature, geothermal can generate a stable baseload power around the clock to complement more variable output from other green sources, including wind and solar.

Indonesia has recognised that geothermal power must play a central role in its efforts to meet soaring energy demand, achieve its goal of sourcing 23 per cent of its energy from renewables by 2025, and cut carbon emissions to net-zero by 2060.

Increasing domestic capacity will also help Indonesia cushion itself from the risks associated with its dependence on fossil fuel imports and associated price fluctuations while reducing fossil fuel subsidies, which gobble Rupiah 70.5 trillion (US$4.9 billion) a year.

Indonesia’s idea to draw energy from the bowels of the Earth goes back to the Dutch colonial era. Trial well drilling began at Java’s Kamojang crater as early as 1926, although it would take several more decades until the first generator was installed to produce electricity. By the mid-1980s, several geothermal plants were in operation and explorations on other islands were underway. In 2018, a consortium of Japanese and Indonesian firms completed the US$1.17 billion Sarulla project in North Sumatra, the world’s biggest geothermal power plant at the time with a capacity of 330 megawatts, enough to power 330,000 homes.

As of 2020, Indonesia had 19 existing geothermal working areas and 45 new working areas, while 14 areas had been earmarked for preliminary surveys and exploration, according to government data. A total of 16 geothermal power plants have been built.

Investors stay away

Despite the sheer scale of its potential, the sector has experienced setbacks. The government’s plans for the industry largely hinge on private money, but major policy uncertainties and the government’s adverse pricing regime for renewables continue to deter investors and drive up costs, making geothermal projects less viable.

Due to this poor investment climate, the energy and mineral resources ministry conceded last year, progress on its ambition to install 7.2 GW of geothermal capacity by 2025, a target enshrined in its electricity procurement plan (RUPTL), will be delayed by five years. It is estimated that Indonesia will require US$15 billion in investment to meet this goal.

If Indonesia doesn’t develop a clearer framework, the sector will find it difficult to thrive.

Septia Buntara Supendi, manager, sustainable energy and energy efficiency, Asean Centre for Energy

The list of market restraints is long. Two key obstacles are the lack of favourable rates for the power that developers feed into the grid and the high upfront risks facing firms in the exploration stage. Drilling wells can be a gamble because companies never know exactly how big a geothermal reserve they will find. This clouds the economics of geothermal ventures.

“Pricing has been a problem for renewable energy in Indonesia, especially for geothermal energy, because the development costs are very high,” Florian Kitt, a Jakarta-based energy specialist at the Asian Development Bank told Eco-Business.

Complicating matters further is that geothermal resources are often found in remote areas, further increasing costs. The government will need to throw other renewables into the mix to achieve least-cost electricity generation, Kitt said.

“The government wants to be a world leader in geothermal energy, and it will eventually be, but right now it makes more sense to look at how to best diversify and green Indonesia’s energy supply to meet demand at least cost. Key is an affordable mix of geothermal, solar, wind, hydro, biomass, and other renewable energy sources,” he said.

Indonesia also hasn’t laid the necessary groundwork to draw investment. From inadequate grid management and cumbersome negotiation practices to poorly designed power purchase agreements, there are myriad barriers the nation needs to tackle, according to an ADB report released last year.

While the adoption of international best practices for planning, procurement, contracting and risk mitigation will likely bring down clean energy costs, the government has not adequately “taken into account the dependency of renewable energy costs on the broader regulatory and commercial environment”, according to the bank.

A recent report by the International Institute for Sustainable Development, an independent Canadian think tank, showed that out of the 75 power purchase agreements that clean energy firms had signed with government-owned utility company Perusahaan Listrik Negara (PLN) between 2017 and 2018, 36 per cent had not reached financial closing, and nearly 7 per cent had been terminated.

New hope

To plug the industry’s funding gap, the government has backed research on small-scale geothermal plants that come with smaller investment needs and risks compared to bigger facilities. The state also provides tax incentives and has streamlined previously tedious permit processes. In remote areas, it has engaged communities to improve public acceptance of geothermal development. Local opposition to geothermal plants has hamstrung projects in the past.

The government’s focus on de-risking geothermal exploration to incentivise private investment has been an important step towards increasing geothermal development, according to Kitt.

But a presidential regulation announced last year that is predicted to revitalise the renewables sector remains stuck in limbo. While a draft is on the table, the different ministries are still debating the budgetary impacts of the scheme as the Covid-19 pandemic continues wreaking havoc on the economy, soaking up government resources.

The regulation is meant to fix the pricing mechanism for geothermal power and mitigate early development risks through fiscal incentives and state-funded well drilling. Under the scheme, energy planners have also proposed a subsidy to close the gap between the geothermal power tariffs and PLN’s basic cost of electricity, a policy previously recommended by the ADB to encourage the state utility to buy more clean energy. At present, caps on PLN’s retail prices act as a strong disincentive for the firm to purchase anything but the lowest-cost electricity, which is typically coal-fired.

“There are massive opportunities in geothermal energy. The sector will be critical for Indonesia to achieve its sustainable energy ambitions,” said Septia Buntara Supendi, manager for sustainable energy and energy efficiency at the Asean Centre for Energy, a think tank based in Jakarta. “But if Indonesia doesn’t develop a clearer framework, the sector will find it difficult to thrive.”

By Tim Ha

Source Eco Business